This website, being one that teaches Polari, talks briefly about how the language was used (and is perhaps still used in one form or another) by entertainers such as British showpeople. However, the history of British travelling showpeople remains largely unexplored within the broader context of British history. For this reason, this article will provide a brief history of British travelling showpeople, dividing their history into two sections demarcated by the establishment of the Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain in 1889.

Before the Guild’s Establishment

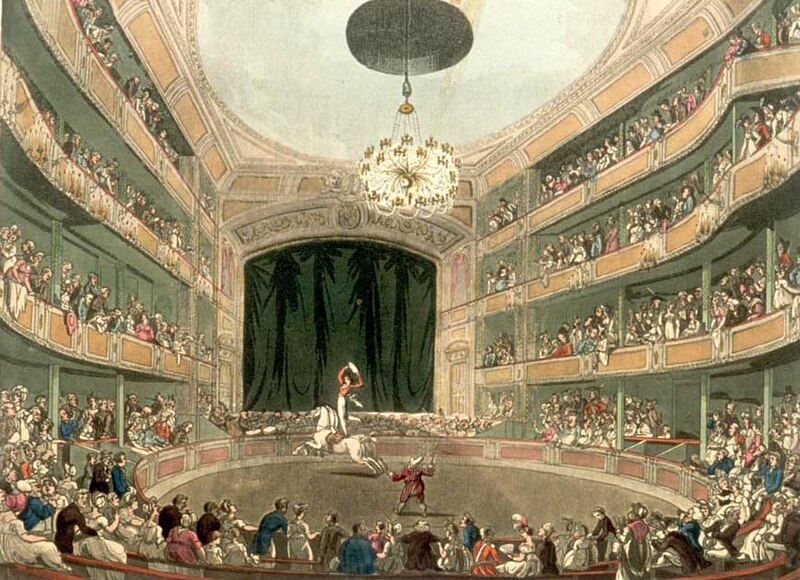

It is difficult to pinpoint a specific time in which British showpeople as a distinct social group came into existence. However, it is reported that circuses were invented in 1768 when a horse-riding instructor and soldier by the name of Philip Astley devised a performance art involving horse-riding in a ring, which soon came to involve acrobatics and clowns (Davis, 2019. p.456; Carmeli, 1988, p. 263). Astley established an amphitheatre in London, and due to its popularity, similar venues began to appear in both Britain and parts of North America (Davis, 2019, p. 457-458). Fairs have much earlier origins, tracing back to medieval times (Hey, 2008, pp. 382 & 404). However, these fairs primarily resembled livestock markets until the 19th century when fairs had become increasingly associated with entertainment (Hey, 2008, pp. 382 & 404).

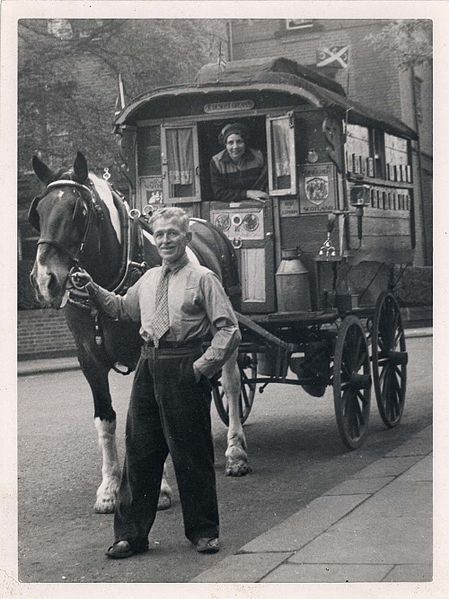

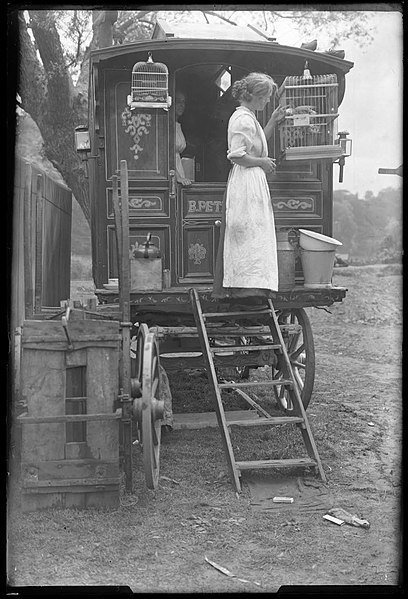

Following the establishment of the circus, many of those who were involved in the presentation of circus performances and funfairs were – and still are – itinerant, travelling from place to place to perform or undertake other relevant tasks (Carmeli, 1988, pp. 258 & 263). With itinerant peoples being nothing new in Britain at the time and Romanichal people (who are traditionally itinerant) existing in Britain from at least the 16th century, travelling showpeople came to be viewed as analogous to Romanichals (Carmeli, 1988, pp. 258-259; Matras, 2010, p.1). Not unlike the Romanichal, British travelling showpeople were viewed somewhat unfavourably in the Victorian era, with many seeing showpeople as representative of a vulgar industry that insulted and distracted from religious sensibilities (Farge, 2021). Another view was that funfairs and circuses were a nuisance to local residents (Assael, 2005, pp. 40-41). Despite this, it was the Victorian era which saw the rise in popularity for circuses and funfairs in Britain as a result of increased industrialisation (Farge, 2021). At the time, a rise in disposable income, the ability to take time off work and increasingly expansive transport networks meant that the broader populace now had more opportunities to go to funfairs and circuses (Farge, 2021). This was at the same time that increased mechanisation in the entertainment industry allowed for circuses and funfairs to operate with relative ease (Farge, 2021).

After the Guild’s Establishment

In 1889, the Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain was established (University of Sheffield, n.d.). Originally called the Van Dwellers’ Association, it aimed to counter the sort of legal actions which had threatened the livelihood of travelling showpeople and resulted in – despite a trend of increasing popularity of circuses and funfairs – the closing down of funfairs such as Bartholemew Fair in 1855 and Greenwich Fair in 1857 (Assael, 2005, pp. 25-26 & 41-43; University of Sheffield, n.d.). The specific legal action prompting the association’s establishment was the Moveable Dwellings Bill of 1888, which was introduced by an Evangelical lawmaker by the name of George Smith (Assael, 2005, pp. 41-43; University of Sheffield, n.d.). This bill included proposals to mandate compulsory school attendance for children in itinerant communities, the registration of caravans, and the ability for authorities to enter caravans between 6am and 9pm on any given day to inspect for issues related to overcrowding, health and ‘moral irregularities’ (Assael, 2005, pp. 41-43; University of Sheffield, n.d.). It is also stated that the Guild was established to – for whatever reason – distance travelling showpeople from ‘gypsies’ (Farge, 2021; University of Sheffield, n.d.).

Around a century after the establishment of the Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain, Carmelli (1988, pp. 264-271) noted that travelling showpeople were met with ambivalent attitudes from the broader populace. On the one hand, the short-lived presence of a circus provided a popular form of entertainment and fascination for the residents of any given town (Carmelli, 1988, p. 267). However, it was also noted that travelling showpeople occupied a marginal position in society (Carmelli, 1988, p. 264). Parking licenses for travelling showpeople were often rejected by local councils, with ideas of circuses being a nuisance, irrelevant and a threat to animal welfare existing in broader society (Carmelli, 1988, pp. 264-267).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article presents a brief history of travelling showpeople in Britain, dividing their history into two periods demarcated by the establishment of the Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain. As it can be seen above, a persistent theme in the history of travelling showpeople is one of ambivalent attitudes from broader society. Whilst providing a popular form of entertainment to the broader populace, travelling showpeople have been historically subject to unfavourable legal actions and societal stigmas which have contributed to their marginalisation.

Sources

Assael, B. (2005). The Circus and Victorian Society. University of Virginia Press.

Carmeli, Y. S. (1988). Travelling circus: an interpretation. European Journal of Sociology, 29(2), 258-282. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24467560.

Davis, L. (2016). Between Archive and Repertoire: Astley’s Amphitheatre, Early Circus, and Romantic-Era Song Culture. Studies in Romanticism, 58(4), 451-479. https://doi.org/10.1353/srm.2019.0036.

Farge, H. (2021, June 22). The language of the fairground community: secrets of Parlyaree. University of Sheffield. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/library/news/language-fairground-community-secrets-parlyaree.

Hey, D. (2008). The Oxford Companion to Local and Family History (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Matras, Y. (2010). Romani in Britain: The Afterlife of a Language. Edinburgh University Press.

University of Sheffield. (n.d.). The Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain (Established 1889). Discover Our Archives. https://archives.shef.ac.uk/agents/corporate_entities/8.

Images

Fenwick, A. J. (n.d.). [Photo of showman’s caravan]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Circus_Showman%27s_caravan2.jpg. Held by Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums.

Fenwick, A. J. (n.d.). [Photo of a showwoman tending to a birdcage]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Young_lady_and_birdcages_(7589460818).jpg. Held by Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums.

Fenwick, A. J. (1950). [Photo of travelling showpeople]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Desert_Dream_caravan_on_the_road,_1950_(7589461204).jpg. Held by Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums.

Rowlandson, T. & Pugin, A. (n.d.). [Drawing of Astley’s Amphitheatre in London]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Astley%27s_Amphitheatre_Microcosm_edited.jpg.

Leave a comment